A former La-7

Ask Mr. Ivan Kozhedub. He had 64 kills plus he piloted the LA-7.

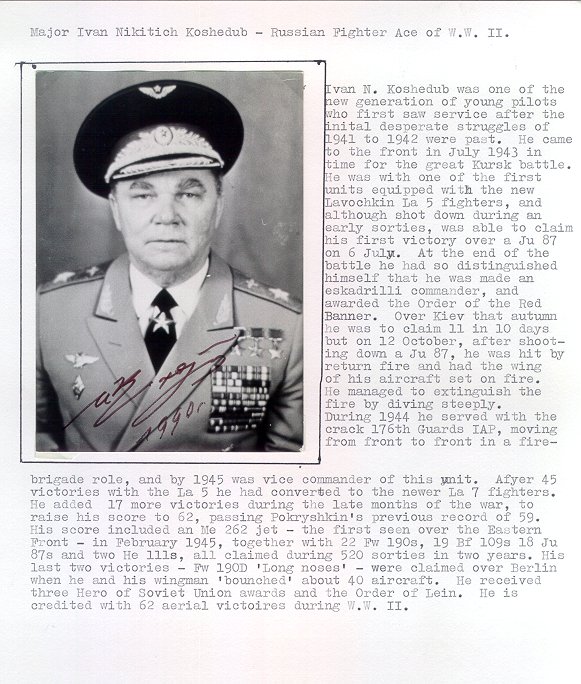

By Jon Guttman for Aviation History Magazine Air Marshal Ivan Kozhedub was one of only two Soviet fighter pilots to be awarded the Gold Star of a Hero of the Soviet Union three times during World War II. The other, Aleksandr Pokryshkin, had flown from the German invasion in the summer of 1941 through the end of the war, during which time he scored 59 aerial victories in MiG3s, Bell Airacobras, Lavochkin La-5s and Yakovlev Yak-9Us.

Ironically prevented from fighting because his skill as a pilot made him more useful as an instructor, Kozhedub did not fly his first combat mission until March 26, 1943. On February 19, 1945, he became the only Soviet pilot to shoot down a Messerschmitt Me-262 jet fighter and, on April 19, 1945, he downed two Focke-Wulf Fw-190s to bring his final tally to 62--the top Allied ace of the war.

In contrast to Aleksandr Pokryshkin, Ivan Kozhedub is associated with a single fighter type, the series of radialengine, wooden aircraft designed by Semyen Lavochkin. The last of them, La-7 No. 27, has, like its pilot, survived to graceful retirement-in the airplane's case at the Monino Air Museum.

AH: Could you share with us something of your youth and education? Kozhedub: I was born on June 8, 1920, in the village of Obrazheyevska, Shostka district of the Sumy region in the Ukraine. I was the youngest of five children in our family. I had a hard time when I was a child and never had enough to eat as a teen-ager. I had to work all the time back then. My only toys were handmade stilts, a rag ball and skis made of barrel planks.

In 1934, I finished a seven-year school. At first, I wanted to go to art school in Leningrad, but realized that I'd hardly get through. For two years, I attended a school for young workers. In 1940, I graduated from the Shostka chemical technical school.

AH: When, then, did you develop an interest in aviation? Kozhedub: A craving for the skies, which I could not identify as such at the time, was probably born in my heart when I was around 15. It was then that airplanes from a local flying club began to crisscross the sky over the village of Obrazheyevska. Later on, no matter what I might be doing--solving a difficult math problem or playing at ball--I would forget instantly about everything as soon as I heard the rumble of an aircraft motor.

AH: A lot of people are fascinated by aviation, but what caused you to take the big step from enthusiast to participant? Kozhedub: In the 1930s, the Komsomol (Young Communist League) was a patron of aviation and, naturally enough, we were all crazy about flying. I remember well the words of my school teacher: "Choose the life of an outstanding man as a model, and try to follow his example in everything." For me, a boy of 16, and for thousands of other Soviet teen-agers, the famous pilot Valery Chkalov was such a man. The whole world admired his bold long distance flights in the Tupolev ANT-25, such as his 1936 flight from Moscow to Udd Island, Kamchatka--9,374 kilometers in 56 hours, 20 minutes--or his shorter but more hazardous flight of 8,504 km in 63 hours, 16 minutes from Moscow to Vancouver, Wash., via the North Pole, on June 18-20, 1937. He was also a fearless test pilot, and it was during a test flight that he lost his life on December 15, 1938.

Realizing full well that it would be difficult to attend a technical school and learn to fly at the same time, I still filed an application at the local club. That was in 1938, when the Japanese violated the Soviet frontier near Lake Khasan. That fact strengthened my desire to receive a second profession that would be needed in the event of war.

AH: Can you describe your training? How many flying hours did it take to qualify as a pilot? Was your training typical for a Soviet pilot, civil or military? Kozhedub: At the beginning of 1940, 1 was admitted to the Chuguyev military aviation school. It was the beginning of a new life for me. At the flying club, we had just been working on the ABCs, whereas at the school, serious training was buttressed by tough military discipline. At our school, to become a pilot you had to fulfill a flying quota of about 100 hours.

AH: What was your perception of the state of Soviet aviation and general military preparedness prior to and in the months following the German invasion? Kozhedub: Of course, we were young at the time. We believed that our country was absolutely ready to rebuff any aggression. Any fighting on our own territory was considered unthinkable. Everything we read or heard over the radio about the war to the west seemed very remote to us. Needless to say, at that time we did not know that more than 40,000 of the most talented military leaders had been killed by Stalin's purges a few years earlier. We realized what had happened much later. Every report about the retreat of our troops made our hearts bleed.

AH: Did the Soviet Army Air Force (VVS-RKKA) undergo any changes in structure, philosophy or strategy during the war years? If so, what changes did you notice? Kozhedub: The experience of hostilities in the early months of the war required a change in the tactics and organizational structure of fighter aviation. The famous formula of air-to-air combat was: "Altitude-speed-maneuver-fire." A flight of two fighters became a permanent combat tactical unit in fighter aviation. Correspondingly, a flight of three planes was replaced with a flight of four planes. The formations of squadrons came to include several groups, each of which had its own tactical mission (assault, protection, suppression, air defense, etc.). The massive use of aviation, its increasing influence on the course of combat and operations, required that its efforts be concentrated in those major specialties.

Fighter air corps making up part of air armies were set up for that purpose. Hundreds of fighters took part in crucial tactical and strategic operations. Quite often, air-to-air combat developed into a virtual air battle. The arsenal of combat methods used by Soviet fighter aces came to include vertical maneuvers, multilayered formations and others. Out of the 44,000 aircraft lost by Germany on the Soviet-German front, 90 percent were downed by fighters

AH: Did you request a transfer to the front as a combat flier, or were you given such duty by your commanders? Kozhedub: I requested a transfer to the front more than once. But the front required well-trained fliers. While training them for future battles, I was also training myself. At the same time, it felt good to hear of their exploits at the front. In late 1942, I was sent to learn to fly a new plane, the Lavochkin LaG-5. After March 1943, I was finally in active service.

AH: What was your first impression of the LaG-5, your first combat aircraft? Did it have any special quirks or idiosyncrasies? Kozhedub: I got LaG-5 No. 75. Like other aircraft of our regiment, it had the words "Named after Valery Chkalov" inscribed on its fuselage. Those planes were built on donations from Soviet people. But my plane was different. Other fliers had aircraft with three fuel tanks, which were lighter and more maneuverable, whereas my fivetank aircraft was heavier. But for a start its potential was quite enough for me, a budding flier. Later on, I had many occasions to admire the strength and staying power of this plane. It had excellent structural mounting points and an ingenious fire-fighting system, which diverted the exhaust gases into the fuel tanks, and once saved me from what seemed certain death.

AH: Did you know anything of the less-successful predecessor of the LaG-5, the LaGG-3? Did you ever fly that plane and, if so, how did it compare with the later Lavochkins? Kozhedub: All those planes were one family. So naturally enough, every new generation flew higher and farther. However, I did not fly the LaGG-3 myself. I know this plane was designed by Lavochkin together with his colleagues, Gorbunov and Gudkov, in 1940. It had a water-cooled engine, and like all early models, was not faultless. Its successors, the La-5 and La-7, accumulated combat experience. They had air-cooled engines and were much more reliable.

AH: To what unit were you first assigned? How were you received by the men of the regiment? Kozhedub: My first appointment was to the 240th Fighter Air Regiment (Istrebitelsky Aviatsy Polk, or IAP), which began combat operations on the first day of the war, on the Leningrad front. Since many graduates of the Chuguyev school served there, I did not feel out of place, not even at the beginning. Our pilot personnel included people of many nationalities. There were Belorussians, Tartars, Georgians, Russians and Ukrainians. We were all like one big family.

AH: What was the typical strength and organization of a Soviet VVS regiment (Polk) or squadron (Eskadril) during World War II? Kozhedub: Since the war was teaching us its bitter lessons, we had to change tactics as we went along. Thus, considering the experience of the first battles, the Air Force went over from 60-plane regiments, which appeared to be too heavy, to regiments consisting of 30 fighters (three squadrons). Practice showed that this structure was better, both because it made the commander's job easier and because it ensured higher flexibility in repelling attacks.

AH: Your first week of combat was over the Kharkov sector, during the last great Soviet defeat prior to the decisive battle of Kursk. Allegedly, you yourself were badly shot-up during your first combat by German fighters. What was the state of morale among you and your comrades at this time? PAGE CUT